More Than a Third of Volunteers in a Consumer Reports Study Found Errors in Their Credit Reports

Here’s how to find and fix mistakes and avoid paying for a ‘free’ report

When Victoria Ross’ husband of 40 years died of a heart attack last August, she had to push through her grief to focus on her finances, sell the family home, and downsize into a condo. When she thought everything was settled, the Wintergreen, Va., resident applied for a car loan.

But a major error in one of her credit reports, from TransUnion, stopped her in her tracks.

It mistakenly showed that a PayPal credit card she’d paid off still had a balance due of about $1,200—an error she said hurt her credit score. The other two credit bureaus, Equifax and Experian, correctly reported the account as paid off and closed, she says.

TransUnion’s mistake meant she didn’t qualify for a low-interest rate at the car dealership. “Instead, they gave me a 12 percent rate, which would have increased my monthly payment by more than $100,” Ross says. “I’m on a fixed income, so every dollar counts.”

What’s more, consumers reported often facing roadblocks correcting errors or even just accessing their reports.

As the post-pandemic economy sputters back to life, and through no fault of their own, the broken system can mean consumers have valuable opportunities denied to them, says Syed Ejaz, the financial services policy analyst at CR who conducted the study. “The American dream of owning a home or getting an education or even a job is at risk for those who find errors in their reports and struggle to get them corrected,” he says.

The large number of errors that CR volunteers, including Ross, found in their reports is a “real sign that the credit reporting system is failing American consumers,” says Amy Traub, associate director at Demos, a policy and research organization, where she focuses on consumer financial issues. “Credit reporting is part of our public infrastructure—a necessity for consumers who want to participate economically. But three private companies have all the power over our financial destinies.”

When asked about CR’s findings, Francis Creighton—president and CEO of the Consumer Data Industry Association, the trade association that represents the credit bureaus—challenged the results.

“We strongly caution against drawing conclusions from non-empirical surveys of consumers, such as this,” Creighton says. “The credit reporting industry takes data accuracy extremely seriously, and improvements to the system cannot be achieved by relying on questionable and skewed data studies.” He also says that the “CDIA and our members are proud of our high accuracy rates” and that “we are committed to continually improving the accuracy of credit reports.”

CR’s recent analysis is not the only evidence of a high rate of errors in credit reports. A nationally representative survey conducted by CR in January 2021 (PDF) of 2,223 adults found that 12 percent of people who had ever checked their credit reports said they found errors, with 57 percent able to get their errors corrected after filing a dispute. And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal agency tasked with protecting Americans from deceptive financial practices, reports that credit report errors are common—and the number reported to the agency more than doubled between 2019 and 2020.

Beyond outright mistakes, CR’s volunteers identified other troubles, too. One particularly irksome one: security questions that are too difficult to answer or that are based on outdated or incorrect information, which can block or delay access to the reports.

Others said that they sometimes had to provide credit card information or that they inadvertently signed up for credit-monitoring services costing close to $30 per month. And canceling those services and getting refunds was often complicated and time-consuming.

Here we’ll explain what other consumers like Ross faced, and what you can do if you find errors in your own report.

Common Mistakes, Big Problems

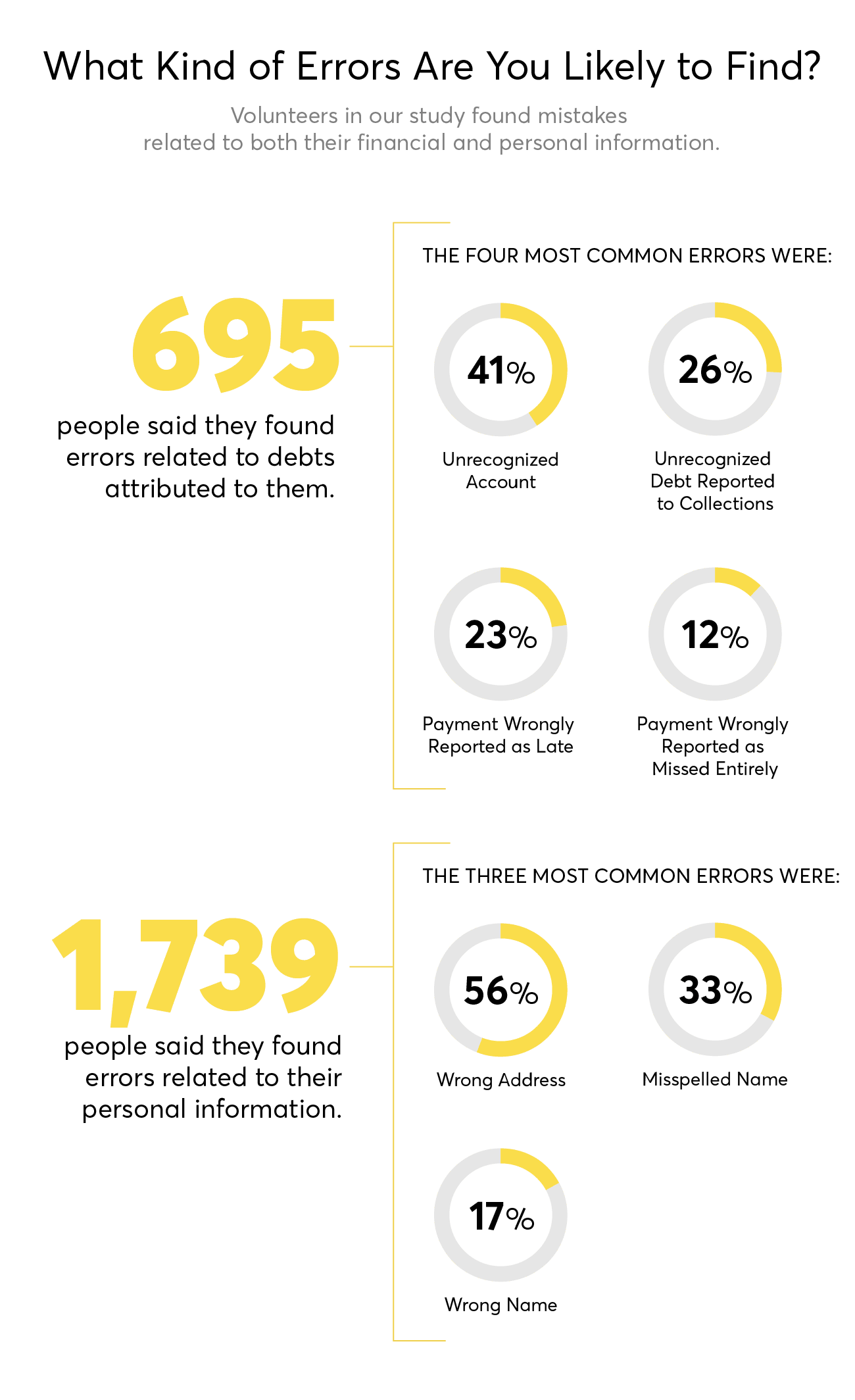

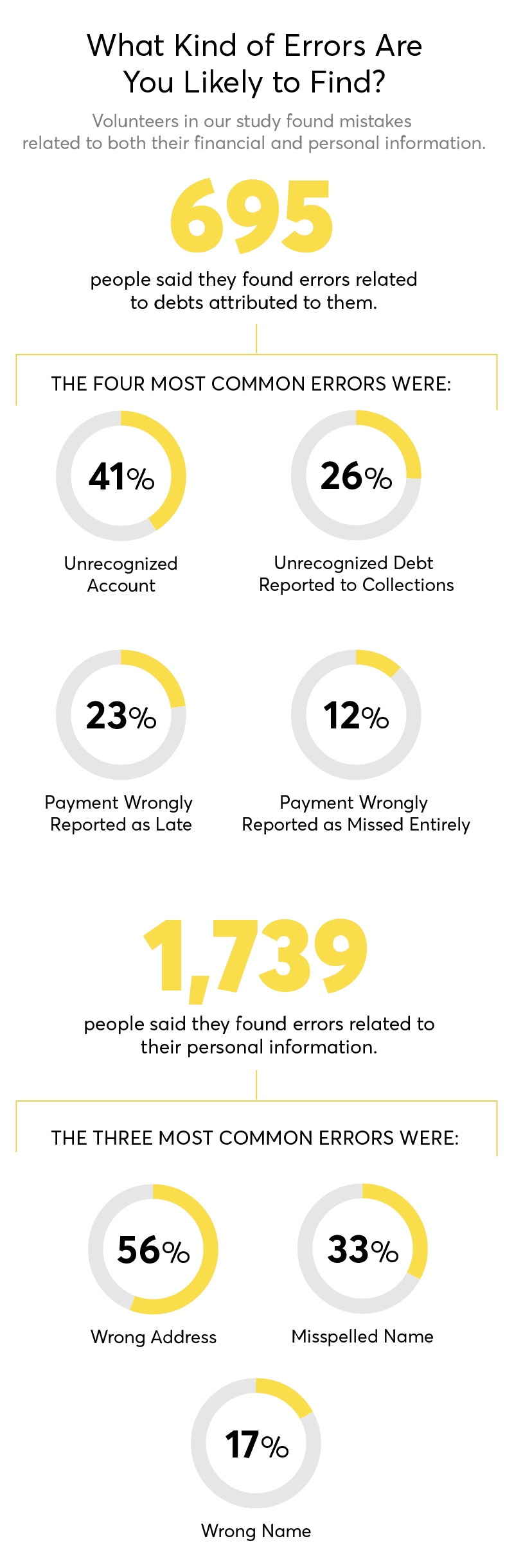

For about 1 in 10 people in the CR study, errors like the one Ross faced were related to their financial data: unrecognized payments, payments wrongly reported as late, or debt in collections mistakenly listed in their name.

Those sorts of errors could easily lower a person’s credit score, Ejaz says. And in some cases, such as when debt is reported as in collections or payments are reported as late, the drop in a score could be tremendous—as many as 100 points.

Mistakes in personal information were even more common. Joseph Pedulla of Boston says that after his bank account was hacked several years ago, a fraudulent mailing address—a location in Ohio where he’d never lived—wound up on his credit reports. It took several years, he says, to get the address removed on all three reports.

Particularly troubling were errors in reports among some people who had sought financial help during the COVID-19 pandemic. Legislation passed in the early days of the crisis offered forbearance to people with certain student loans and mortgages, meaning they could put off payment for several months with no penalty. But 15 percent of the people in CR’s study who said they had an account in forbearance also said their accounts were reported as “not current.”

Denied Entry

While some people in CR’s study were frustrated by the errors in their credit reports, others found it confusing or almost impossible to get their report in the first place. Ten percent said trying to get their report was “difficult” or “very difficult,” with some saying they were locked out for failing to answer a credit bureau’s security questions.

Kathleen Melville-Hall of Alpena, Mich., says that’s what happened to her when she couldn’t remember what year she’d gotten a car loan or had opened a certain credit card and, as result, failed the online security quiz. She was instructed to make copies of her driver’s license and Social Security card and send a request for her report via snail mail instead. She was worried that sensitive information could be stolen in transit. (She says she received reports from all three credit bureaus after several weeks.)

I answered the questions correctly, but because it didn’t match the wrong information they had on file, they wouldn’t allow me to access my credit report.

Dallas-Fort Worth

Credit bureaus have turned to requiring such detailed information in part because that is more secure than asking about, say, your mother’s maiden name, says Ed Mierzwinski, senior director of the federal consumer program at U.S. PIRG, a policy and research organization, and a CR board member. “But who remembers how much their mortgage payment is, or which bank serviced your mortgage 10 years ago, because they get moved around so often?”

Worse, sometimes the security information you are asked about is based on inaccurate dasuta in your report, according to several volunteers. For example, Lori Vann-Guthrie of Dallas-Fort Worth says TransUnion wouldn’t provide online access to her report. “I answered the questions correctly, but because it didn’t match the wrong information they had on file, they wouldn’t allow me to access my credit report.”

A CFPB spokesperson confirmed that “it is not an uncommon problem” for consumers to report being locked out of their credit reports because of problems answering security questions.

Surprise Charges

During the pandemic, credit bureaus are allowing consumers to get a free copy of their credit report every week through April 20, 2022, not just annually, as they had in the past.

But some people in CR’s study said that when they tried to access their supposedly free report, they found that they had to provide credit card information and pay up, anywhere from $1 to $30 or more, to get their report.

For example, Victoria Ross of Virginia said when trying to sort out her PayPal credit card problem and get a copy of her free report, she inadvertently signed up for a monthly TransUnion credit monitoring subscription for $30. “I have a college degree, and I can read,” Ross says, “but I was completely confused into signing up for it.” (After CR asked about the subscription, TransUnion refunded Ross the fee.)

They not only put the burden of monitoring reports on customers’ shoulders, but then they charge them for accessing their own information.

Senior director of federal consumer program at U.S. PIRG

Robin Singletary, a study participant from Wenatchee, Wash., said he had a similar experience after being locked out of his Equifax report and then trying with TransUnion, where he accidentally signed up for a monthly service that charged him about $25 for the first month. “I immediately canceled the subscription and had to call the helpline to get this charge removed from my card,” he says.

Mierzwinski at U.S. PIRG says credit bureaus take advantage of confused consumers. They “not only put the burden of monitoring reports on customers’ shoulders, but then they charge them for accessing their own information,” he says. “Basically, the companies have turned their own failures into a business model. You have to pay to do the work for them.”

How to Find, Dispute, and Fix Problems

Ejaz at CR recommends periodically taking advantage of the free credit reports now being offered by all three credit bureaus by going to AnnualCreditReport.com, the site recommended by the CFPB. If you find an error in your report, you should get it corrected, though doing that is not always easy or fast. Here’s what to do.

First, you need to file complaints with each of the three credit bureaus, not just one, because they don’t communicate with one another.

Do this in writing, sending a letter and any supporting materials via certified mail. That starts a paper trail and can help ensure that the credit bureaus follow federal guidelines for a timely response. By law, the credit bureaus have approximately 30 days to respond.

While it might be tempting to just fill out an online form at the credit bureau to dispute an error, doing so could oversimplify your situation by requiring you to choose among predetermined check boxes, says Andy Milz, a consumer protection attorney in Philadelphia. Milz also worries that by submitting your dispute online, you could unwittingly waive your right to sue as an individual or in a class-action suit if there is widespread, substantial harm, he says.

If you lose the dispute, you can file again—and if you do, include additional information about your situation. Simply resubmitting could automatically get your dispute denied because it might seem like a duplicate submission.

Did you check your credit report and find errors?

If so, what was your experience? Share your story.

If that doesn’t work, you can file a complaint on the CFPB’s website to get your situation investigated, though it’s unclear how long that could take.

If the problem is severe or vexing enough, consider hiring an attorney experienced in federal consumer credit law to further press your claim in court against the credit bureau or financial institution. The Fair Credit Reporting Act gives consumers this right. And know this: If a company is found in violation, your legal fees might be automatically covered. Most law firms won’t require payment up front to review your case.

Find an attorney at the National Association of Consumer Advocates website. In cases of identity theft you have additional rights, including the right to obtain detailed documentation about accounts improperly opened in your name.

Editor’s Note: This article was updated to remove conflicting language indicating that Victoria Ross’ refund was still in progress.