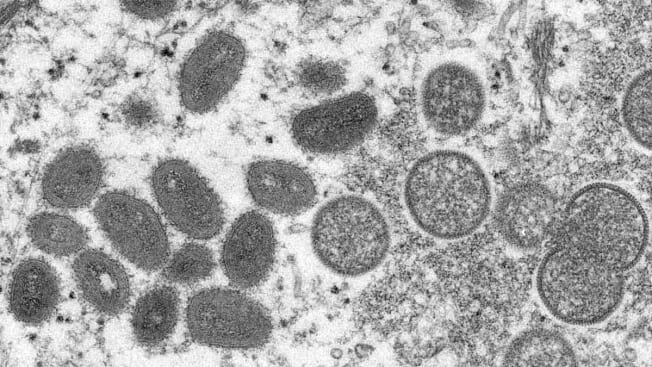

Your Questions About Monkeypox, Answered

The ongoing outbreak is the largest to occur outside of the countries where the virus usually circulates

The world is currently experiencing the largest outbreak of the disease known as monkeypox outside of the countries where it regularly circulates.

On Aug. 4, facing rapidly growing case numbers, health officials declared the outbreak a public health emergency in the U.S. "We’re prepared to take our response to the next level on this virus," said Xavier Becarra, Secretary of Health and Human Services, at a press conference.

A few weeks earlier, in late July, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, calling for countries around the world to respond to the outbreak and take steps to stop human-to-human transmission, protect vulnerable groups, and intensify surveillance efforts to detect the disease.

Officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say they are aware of more than 25,864 cases that have been identified since May outside of the West and Central African countries where monkeypox is endemic. The cases—many of which have no known links to travel to these regions—have been found in at least 76 countries that have not historically reported monkeypox, including Australia, Canada, Israel, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S.

So far, the CDC has identified at least 6,617 cases in the U.S. This is probably an undercount, and as awareness of the virus increases, experts think more cases will be identified.

The current outbreak is a unique situation because this illness—which is related to smallpox though is not as contagious or deadly—has never spread this widely before. This is the first time cases and clusters of infections are simultaneously appearing in endemic and nonendemic countries.

The current risk to public health in European countries is considered high, according to the WHO. In the U.S., the risk to the average person is low at this time, but some people in social networks where monkeypox is transmitting could be at higher risk. According to the WHO, the public health risk could increase in all areas around the world, reaching a global high-risk situation, if the virus becomes more widespread.

On June 28, U.S. public health officials announced plans to make vaccines that can protect against monkeypox more accessible to people at higher risk of exposure. Smallpox vaccines, which can also work against monkeypox, will be accessible to known contacts of cases and to others who have attended events or venues where monkeypox was known to spread. (See more on who qualifies and is at higher risk below.) The public health emergency declaration announced Aug. 4 could allow health officials to authorize tests, treatments, and preventative measures like vaccines under an emergency use authorization. It should also make it easier for health agencies to access funding and data to fight the outbreak.

Ever since COVID-19 emerged, any unexpected disease outbreak understandably raises alarms for many. To explain the current risks, we’ve consulted with infectious disease and public health experts to answer common questions.

Is Monkeypox a New Disease?

No, we’ve known about it for decades.

The virus was first identified in 1958 in Denmark, in monkeys imported from Singapore, according to Daniel Lucey, MD, a clinical professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, N.H., who spoke at a June 1 briefing by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on monkeypox. While the virus was first identified in monkeys, hence its name, experts think the host species it came from originally is most likely some kind of rodent.

How Is the Situation Now Different From Past Monkeypox Outbreaks?

Since smallpox vaccination ended, monkeypox cases have been reported in 11 countries in Africa, with most outbreaks occurring in rural rainforest regions of Congo, according to the WHO. Nigeria recorded its first cases in 40 years in an outbreak in 2017. By December 2018, there were 132 confirmed and likely cases in Nigeria, with seven deaths, according to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control.

There have also been monkeypox outbreaks outside the endemic regions prior to the current situation. In 2003, there were 47 confirmed and probable human cases in six U.S. states that were linked to prairie dogs that had been stored in an exotic pet store with rodents imported from Africa, such as tree squirrels and the African giant pouched rat. Travel-linked cases have occurred in the U.S. and other countries from time to time, including two in 2021 in travelers returning to the U.S. from Nigeria.

But this time, new cases are being found quickly in many countries around the world, and many patients appear to have caught the virus without having traveled to West or Central Africa.

Plus, there don’t appear to be clear connections among all these cases, says Paritosh Prasad, MD, director of the Highly Infectious Disease Unit at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“I suspect this is not all rapid transmission,” Prasad says. “I think it’s probably been transmitting for a little while under the radar, masquerading as things that are more commonplace.” It’s possible, he says, that some of these cases could have initially been thought to be herpes, shingles, chancroid, or syphilis, which can all cause lesions on the body.

The farther the virus spreads, the harder it is to identify and isolate cases. The continued emergence of new cases and the appearance of cases in new countries indicate that the virus has been circulating without being detected by surveillance systems for some time, according to the WHO.

The current outbreak is likely a consequence of the fact that monkeypox has been allowed to spread unchecked in Africa in recent years, two Nigerian scientists wrote in a commentary published in the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology on July 20. This “should be a wake-up call,” they wrote. “It should also serve as a reminder that in an interconnected and globalized world, no region or country is safe from zoonotic pathogens like [monkeypox] unless the virus is contained in endemic regions.”

The question now is whether it’s possible to curtail the ongoing outbreak. “We are working very hard to contain it, [but] it is too early to know whether monkeypox could become endemic” in the U.S., Capt. Jennifer McQuiston, DVM, deputy director for the CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said during a June 3 press call.

What Are the Symptoms of Monkeypox, and How Does It Spread?

A monkeypox infection generally begins with typical viral symptoms, including fever, headache, muscle aches and backache, chills, exhaustion, and swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin, on one or both sides of the body. That swelling is one of the main differences between the initial symptoms of monkeypox and those of smallpox. These symptoms usually occur within seven to 14 days of exposure.

A day to a few days after the first symptoms, a rash appears (see images below). It may start on the face, according to the CDC, though it can appear in other places. It can cause lesions on the palms of hands and soles of feet, which is rare among viral infections, according to Prasad. And while it can cause lesions to appear all over the body, those lesions may appear in only a small concentrated area. These usually begin as lesions with a flat base, developing into small, fluid-filled blisters and then pustules—a pus-containing rash—before drying out.

In the current outbreak, doctors have noticed that in some cases, people have developed a rash before having any other viral symptoms, according to the CDC’s director, Rochelle Walensky, MD, who spoke at a June 10 press briefing. In some cases, people haven’t had any symptoms at all aside from the rash. And in some cases, people have had few lesions or only a single one.

Still, even when limited, these lesions can cause severe debilitating pain, said Mary Foote, MD, medical director of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Office of Emergency Preparedness and Response, during an IDSA press call July 14. The lesions can cause long-term scarring, according to McQuiston. Most people recover without treatment in two to four weeks, but the virus can be more dangerous or deadly for children or immunocompromised people.

A case study published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) from 528 cases in the current outbreak found that 13 percent required hospitalization, with many patients seeking treatment for rash, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and sore throat.

In this particular outbreak, many patients have had these lesions appear in the genital or perianal regions, which may have led people to assume they were from a sexually transmitted infection. And some people recently diagnosed with monkeypox have also had STIs, according to Walensky. That means the presence of an STI shouldn’t be used to rule out monkeypox, and people who test positive for monkeypox should still be tested for other STIs.

Monkeypox isn’t a sexually transmitted infection, but it can be spread through close physical contact with its signature lesions. Intimate physical contact could spread the virus. But anyone in close contact with an infected person—or who handles bedding or clothing that touched the rash—could be vulnerable. In other monkeypox outbreaks, people have often passed the virus on to family members, for example.

It’s not exactly clear how many people the typical person infected with monkeypox transmits the disease to, a figure referred to as R0 or R-naught. Estimates made during the 1970s put that number at less than one, meaning that an infected person would typically transmit disease to less than one other person, on average. But the contemporary number could be higher, with the average person transmitting it to between 1.1 and 2.4 other people, according to a 2020 study published in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

It’s also possible that people could spread the virus through droplets in a cough if they have lesions in their mouth or throat, though monkeypox isn’t a respiratory virus like COVID-19 or the common cold. This could be a particular risk for healthcare workers caring for someone with an active infection, according to McQuiston, speaking at another CDC briefing May 23. But monkeypox is usually spread via close contact, not casual contact like walking by someone in a grocery store, she said.

Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx

Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx

Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx Source: Image used with permission from VisualDx

What If You Think You’ve Been Exposed or You Have a Rash?

So far in this particular outbreak, many of the people infected have identified as men who have sex with men, including approximately 98 percent of cases in the NEJM study. This could be due to interconnected social networks, or it could be that these have been some of the first cases identified because healthcare providers working with this population have a broad knowledge of infectious diseases, according to a CDC report published June 3. But anyone in close contact with an infected person could be at risk, so doctors are urging people to be aware and to contact their physician if they’re concerned.

“If you develop symptoms like a rash or flulike symptoms pre-monkeypox, you would be calling your clinician and explaining what’s going on,” said Erica Shenoy, MD, PhD, medical director of the Regional Emerging Special Pathogens Treatment Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, at the June 1 IDSA briefing. Do the same thing now, she says. Whether or not it’s monkeypox, it may be something that needs attention and treatment. And if you aren’t feeling well and have symptoms like this, avoid close contact with other people until you have recovered.

Is There a Monkeypox Vaccine?

Yes. Because monkeypox is closely related to smallpox, the two vaccines that are approved for smallpox—ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS, which is also approved by the Food and Drug Administration for monkeypox—can be used. These can be given to people who are at high risk of exposure, including healthcare workers, and also to people in the days after they’ve been exposed. Post-exposure vaccination is most effective at preventing infection in the first four days, according to Shenoy.

In general, the JYNNEOS vaccine is considered preferable because it has a lower risk of side effects. But it’s technically a two-dose vaccine, so people will be able to get only the first dose immediately after exposure.

“With time we’ll get a better sense of the transmission pattern and specific populations at risk,” Prasad says. “Once we have a better understanding, that’ll inform how widely we distribute the vaccines.”

Smallpox vaccines do come with a risk of side effects. For the JYNNEOS vaccine, which there is a more limited supply of, these are relatively mild and include pain, swelling, headache, and fatigue. The more widely available ACAM2000 vaccine can cause heart inflammation—myocarditis and pericarditis—and because it’s an injection with a live virus (related to but still distinct from smallpox and monkeypox), it can potentially cause a more serious infection that can spread to other people. That vaccine shouldn’t be given to infants, pregnant or breastfeeding people, immunosuppressed people, or anyone with certain skin conditions.

Vaccines will be provided to people with confirmed and presumed monkeypox exposure, according to HHS. Along with certain healthcare workers, this includes “those who have had close physical contact with someone diagnosed with monkeypox, those who know their sexual partner was diagnosed with monkeypox, and men who have sex with men who have recently had multiple sex partners in a venue where there was known to be monkeypox or in an area where monkeypox is spreading,” according to an HHS press release. You can check with your state or local public health department to see whether you qualify.

Still, so far, vaccine demand has outstripped supply, Foote said during the July 14 IDSA call.

As of Aug. 4, the HHS and CDC have deployed more than 600,000 vaccine doses to state, city, and territorial health departments, according to the HHS. And on July 27, the FDA announced that it had finished inspecting and approved 786,000 new doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine for distribution, which should help alleviate some of the pressure. An additional 500,000 doses are expected to become available in the fall.

On Aug. 4, FDA commissioner Robert Califf announced that the agency was considering allowing the JYNNEOS vaccine to be given in a new way, injected intradermally, into the skin, instead of intramuscularly. This would use a smaller dose, allowing health officials to get five vaccine doses out of vials that currently provide one dose each.

States can also request the ACAM2000 vaccine, of which there are more than 100 million doses available.

Is There a Monkeypox Treatment?

Yes. There are two antivirals that have been approved for the treatment of smallpox that may be used to treat monkeypox, although they have not been approved for that use specifically. It’s not clear exactly how effective these are in humans, but they have been shown to be effective at treating poxviruses in animals, according to the CDC.

Still, while these antivirals have been useful, the drug distribution system for them has slowed access for patients. It requires a significant amount of paperwork, and treatment programs aren’t widely accessible for those who don’t have access to academic hospitals, according to Foote of NYC Health, speaking on the IDSA call.

Could the Virus Mutate?

While nothing is impossible, it’s unlikely that this virus will transform in a significant way, according to Hirsch, the infectious diseases specialist at Mass General. The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is an RNA virus, a type that tends to mutate rapidly—influenza is another of these. Poxviruses like smallpox and monkeypox are DNA viruses, which tend to be much more stable. In the decades that we have known about monkeypox, it hasn’t transformed in a significant way, Hirsch says.

There’s no evidence so far that this virus has become more transmissible, McQuiston said. It’s possible that it has managed to spread this widely in this particular outbreak without becoming more transmissible for at least two reasons. First, transmission seems to have gone unnoticed as the virus spread, and second, there’s little lingering immunity to poxviruses. It has been decades since the last smallpox vaccines were given to the general public.

While genetic sequencing has identified cases that appear to be from different backgrounds, so far, all known cases have been linked to the West African clade of monkeypox.

Should You Be Concerned?

It’s always important to look for signs of any infectious disease, and anyone who thinks they could have been exposed should seek medical attention, Hirsch says. That’s especially important for immunocompromised people.

While the current risk to most people in the U.S. is low, being aware of the disease is important, especially for those in communities where the virus is known to be spreading. The virus is spreading faster and more widely than it ever has before.

As the virus continues to transmit, containing it becomes more difficult. “We certainly expect there will be more cases in the days and perhaps weeks ahead,” Hirsch says.