When it comes to buying an electric vehicle, many consumers might like the idea, but they sometimes balk at the purchase price, which is typically higher than that of an equivalent gasoline-powered vehicle. However, new research from Consumer Reports shows that when total ownership cost is considered—including such factors as purchase price, fueling costs, and maintenance expenses—EVs come out ahead, especially in more affordable segments. (Download a PDF of the fact sheet and the complete report.)

The savings advantage can be compelling in the first few years and continues to improve the longer you own the EV. Our study shows that fuel savings alone can be $4,700 or more over the first seven years.

When comparing vehicles of similar size and from the same segment, an EV can cost anywhere from 10 percent to over 40 percent more than a similar gasoline-only model, according to CR's analysis. The typical total ownership savings over the life of most EVs ranges from $6,000 to $10,000, CR found. The exact margin of savings would depend on the price difference between the gas-powered and EV models that are being compared.

For lower-priced models, the savings on ownership costs over the lifetime of the vehicle (200,000 miles) usually exceed the extra money paid for a comparable EV. For example, a Chevrolet Bolt costs $8,000 more to purchase than a Hyundai Elantra GT, but the Bolt costs $15,000 less to operate over a 200,000-mile lifetime, for a savings of $7,000, our study found. In the luxury segment, operating cost savings are often aided by a tighter price differential. The Tesla Model 3 is priced lower than the gas-powered BMW 330i, and priced only about $2,000 more than an Audi A4. But the savings on operating costs for the Model 3 are about $17,000 when compared with either of the popular German gas-powered sedans.

"No matter how you look at it, the massive lifetime savings potential of EVs could be a game changer for consumers," says Chris Harto, CR's senior policy analyst for transportation and energy, and the leader of the study. "As battery prices and technology improve, prices come down, and more attractive models hit the market, it's only going to get better."

What We Found

Fuel savings: The study shows that a typical EV owner who does most of their fueling at home can expect to save an average of $800 to $1,000 a year on fueling costs over an equivalent gasoline-powered car.

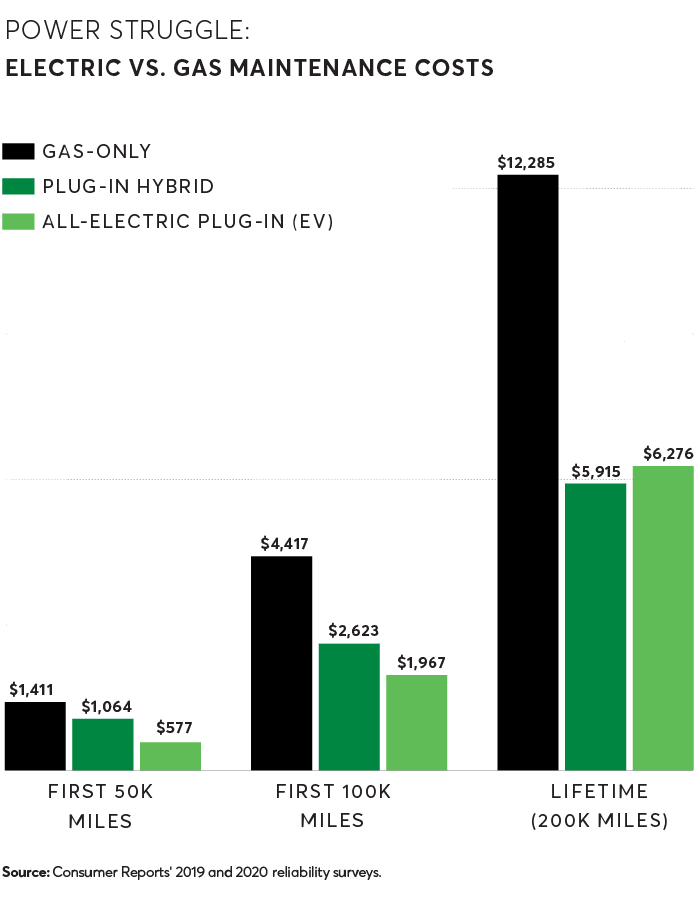

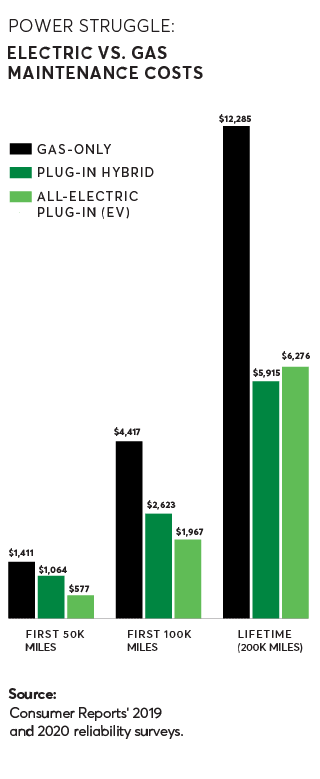

Maintenance and repair: The study also found that maintenance and repair costs for EVs are significantly lower over the life of the vehicle—about half—than for gasoline-powered vehicles, which require regular fluid changes and are more mechanically complex. The average dollar savings over the lifetime of the vehicle is about $4,600.

Depreciation: CR's analysts also found that newer long-range EVs are holding their value as well as or better than their traditional gasoline-powered counterparts as most new models now can be relied on to travel more than 200 miles on a single full charge. As with traditional gasoline-powered vehicles, not all EVs will lose value at the same rate as they age. Class, features, and the reputation of the vehicle's manufacturer all have an impact on depreciation.

Currently, EVs and plug-in hybrids account for less than 2 percent of overall new vehicle sales, although that number has been on the rise since the first viable EV models began to appear on the market almost a decade ago. EVs have been forecasted to constitute anywhere from 8 to 25 percent of the new-car market by 2030. Falling manufacturing costs for the lithium-ion batteries used to power EVs and plug-in hybrids has also brought down prices, although many consumers may still balk at the price difference between EVs and the most fuel-efficient gasoline-powered cars. Tesla announced this month that it would introduce a $25,000 EV within the next year, signaling that EV prices could be falling in the near future.

To be sure, total cost of ownership can vary depending upon region, electricity-service rates, access to charging, and a number of other variables. For example, someone who lives in an extremely cold region with high electricity rates and low EV incentives from state and local government agencies will pay more over the life of the vehicle than someone who lives in an area with a mild climate, inexpensive electricity, and favorable tax incentives.

And Harto says there are several factors beyond price and potential savings that will affect buying decisions. Aside from access to home charging, it's a good idea to look at your state's EV incentives, where applicable. Some states—such as New York and California—are more generous than others. It is also important to consider that some states—such as Arizona, Texas, Alabama, and Arkansas—impose high fees on EVs that could hurt the economics of EV ownership. Also, some EV models are eligible for a federal tax incentive of up to $7,500.

Fuel Savings Can Depend on Car Size

The amount of money a consumer can save on fueling depends on the size of the vehicle and length of ownership, according to the study. Car owners could save an average of $800 the first year, whereas pickup owners could save $1,300 in the same period. Savings in the SUV class falls in between. After seven years of ownership, an EV in the car category will save its owner $4,700, while overall savings for electric pickup owners balloons to almost $9,000. Savings over the lifetime of a vehicle approach $9,000 in the car category and $15,000 for trucks.

Naturally, there are regional differences in gasoline and electricity prices that can make one person's EV fueling price advantage more appealing than another's. But for those who can charge at home—where overnight charging lowers the cost of fueling the vehicle—charging an EV will net savings over gassing up an internal combustion car even in the first year, with big savings piling up after a few years. CR found that in most states, the amount of money EV owners could save on fueling costs were within 10 percent of the national average.

EV Fueling Savings by Class

CR's fueling cost model assumes a $3.02-per-gallon price over the next decade, based on Department of Energy projections, but fuel prices can change quickly, as seen when the nationwide average spiked to the $4-per-gallon range several times in the wake of the 2008 to 2009 recession. A price spike further increases an EV's fueling cost advantage. CR also looked at the effect of long-term lower gas prices on consumer savings. Utilizing the DOE's low gas price scenario—which assumes an average price of $2.33 per gallon over the next 10 years—consumers are still expected to save many thousands of dollars over a typical ownership period, or most of the savings CR projected.

Sam Abuelsamid, the principal research analyst for Guidehouse Insights, a firm that tracks automotive industry trends, noted that at national average prices for electricity, most consumers would come out ahead with an EV, although not necessarily by all that much, depending on the model.

"Bottom line, at current gas prices, the argument for operating-cost savings is complicated if you are comparing similar-sized vehicles with some of the more efficient powertrain options," he says. "If we tax fuel more heavily, it would definitely tilt the equation in the direction of the EV."

Charging-at-Home Sweet Spot

CR found that although longer-range EVs make it possible for most EV owners to do more of their charging at home, where it would presumably cost less than at a public charging station, cars with a 250-mile range were in a "sweet spot" best suited for saving money. At that range, 92 percent of charging can be done at home, requiring only six stops at a public charging station per year. Vehicles with ranges above 300 miles add approximately 20 percent to vehicle cost and battery weight, while only decreasing the amount of public charging needed by 2 percent. Ranges below 200 miles significantly increased the amount of more expensive public charging that would likely be required, to the tune of 11 charging sessions per year for a 200-mile-range EV, and 20 charging sessions for a 150-mile-range model. Most EVs on the market now offer more than 200 miles of range.

Still, higher purchase prices and lack of access to home charging can cause many consumers to shy away from EVs. Although sales have been on the rise since the first viable models appeared in the U.S. in 2011, pure electric and plug-in hybrid sales are still just a sliver of the market.

Abuelsamid and other experts say that in order for consumers to adopt EVs with more fervor, a few things need to happen. First, they need to become less expensive—a scenario that could become reality as battery prices fall. Second, charging needs to be a lot more convenient, he says.

"It's fine today if you live in a single-family home with access to a charger in the driveway or garage, but if you rely on street parking or live in a multi-unit dwelling, it's not practical," he says. "Charging from a public Level 2 (240V) charger takes way too long."

Level 2 chargers are the type typically found in residential settings and are cheaper to use than DC fast chargers, which are generally found at public charging stations and can charge a vehicle in 30 to 45 minutes. The DC chargers cost two to three times more to use.

Modernizing the Grid

An added benefit of EV fueling is its potential impact on the nation's electric grid. Donald Hillebrand, director of the Argonne National Laboratory's energy systems division, says that currently, less intensive electricity use at night means powering down electric plants.

"The grid is a gigantic tool that turns way up during the day and down at night," he says. "It's inefficient because it's got all this equipment that's not running all night and not producing revenue."

Argonne's data show that Americans already have gotten wise to using electricity during times when demand is low and rates are less expensive. During the 1980s, consumers used an average of 3,000 hours of the highest-priced electricity. Over the past decade, that number dropped to 1,000 hours as the average consumer has spread out their electric load to save money.

Hillebrand says that the grid is likely to grow and modernize as EVs become more widespread—not solely because of an EV push but because there are so many other battery-powered technologies people rely on. As more people use the grid to recharge batteries for various products, day and night prices are likely to even out, making EV charging less expensive during the day, he says, adding that there is also likely to be more widespread adoption of home solar panels and electric storage batteries as consumers seek to find new ways to reduce their electricity costs.

"People are going to want solar panels and storage batteries regardless of whether or not there's an EV parked in the driveway," he says. "But it's something that could be a boon to EV sales, and vice versa."